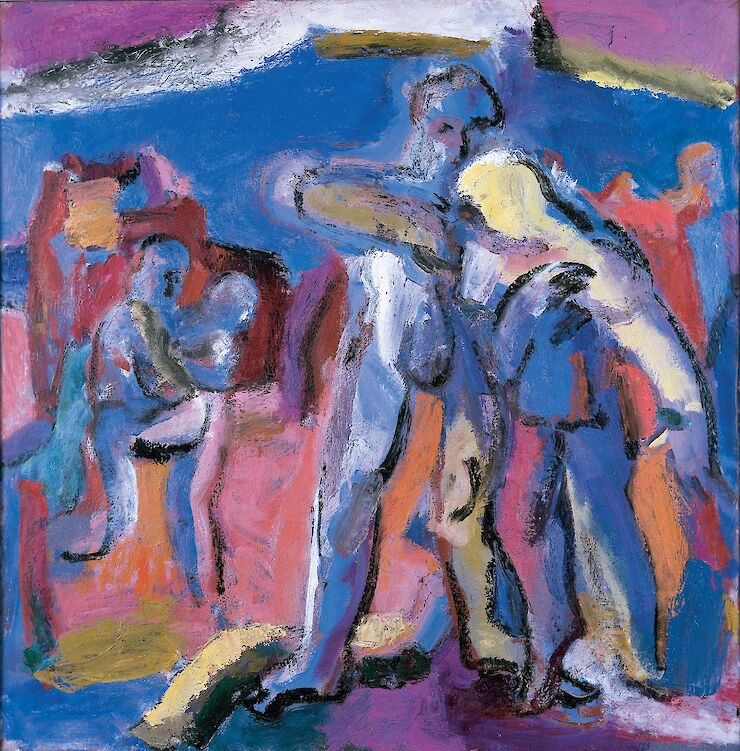

1999, oil on linen, 36" x 45"

The Drawings of Younghee Choi Martin

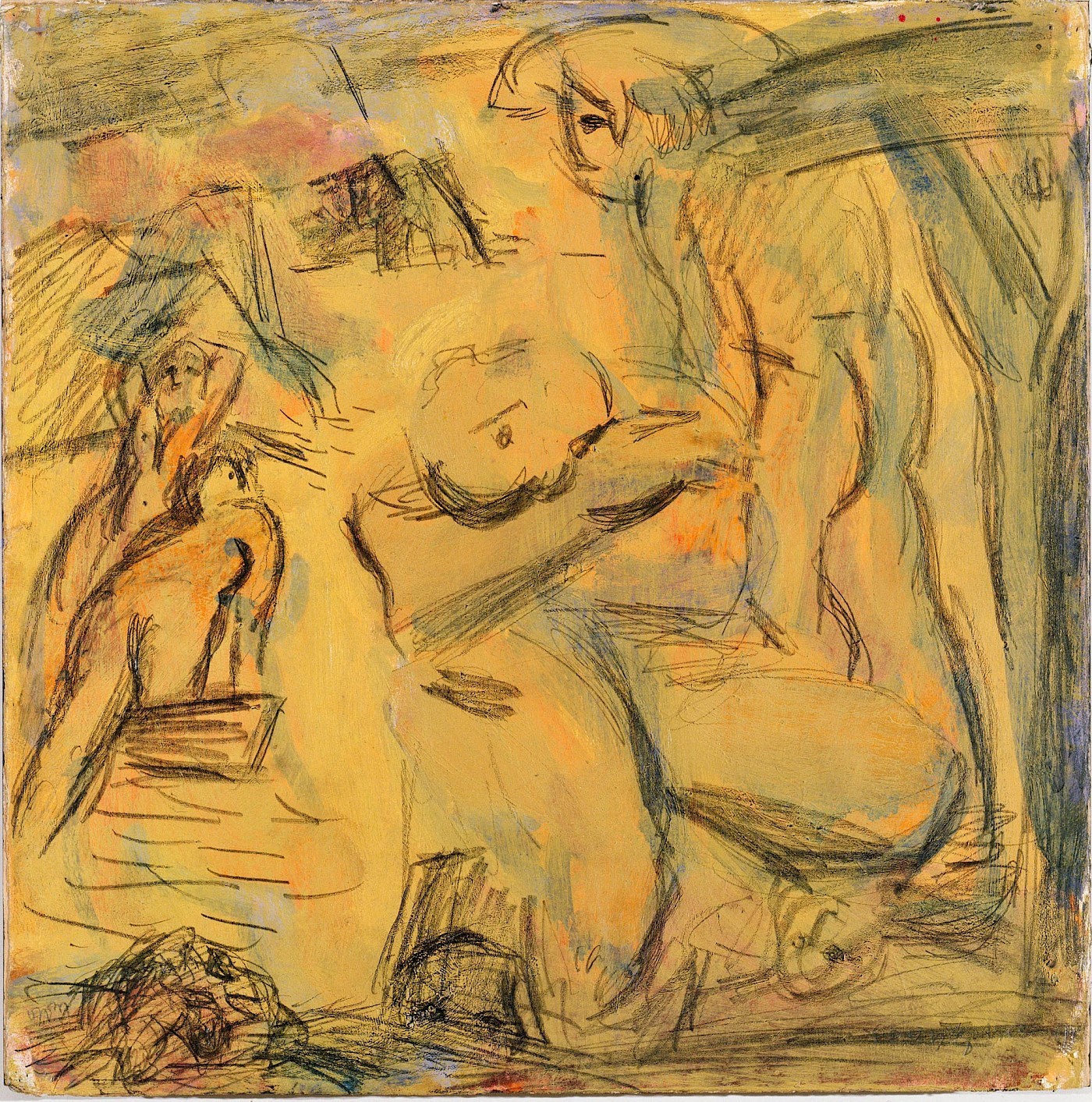

Looking at Younghee Choi Martin’s pencil drawing The Sibyl of Cumae one is at first reminded of the angled lines and shifting tonal areas of a cubist drawing. Then figures that might have come from Michelangelo’s Last Judgment become visible, then rocks and a figure half submerged in water. Finally there emerges a sense of some powerful emotional force to the shadowed foreground figure. These are drawings that release their meanings in sequential stages, drawings that pull the eye back again and again in search of an ultimate resolution that remains elusive.

Younghee’s drawings run parallel to her paintings. “I make drawings before, during and after my paintings. One enriches the other.” The refusal of a traditional relationship of preliminary drawing to final painting reflects the spontaneous, open-ended, and intuitive way she works in both media. Decisions are laid bare so that her considerable reworking, erasing, and layering are part of what the viewer is intended to grasp. The drawings are based as much on value contrast as on line and the lines are drawn several times over so that they too read as values. There are strong evocations of cubism here as well as of Cezanne, in the use of open forms, broken angular lines counterpoised with sections of curves, and tonal areas established in the Cezannesque manner of short parallel lines or strokes.

Running through her drawings is the hint of something previously seen, the suggestion of a kinship with Cezanne’s drawings of bathers or Titian’s late masterpiece, The Flaying of Marsyas. Such resonance is intentional and has been Younghee’s goal since spending her senior year of art school in Rome. She had already taken classes at the Brooklyn Museum Art School and had spent three years at Rhode Island School of Design, a summer at the Provincetown Art School and another summer at the Yale School in Norfolk. However, it was the challenge of the art that she saw in Rome that crystallized her goals—“I was moved by these monumental masterpieces. I wanted to do my own version of these great paintings and see if I could come anywhere close.”

When she returned to the United States, Younghee knew what she wanted to do and knew it would take several decades. She took on a full-time job, eventually becoming an art director at Vanity Fair, and painting at night and on weekends. By 1990 she had enough savings to finance three years of a full-time painting career. Thanks to several solo exhibitions in New York and a developing audience for her work in her native Korea, she has been able to pursue full time painting ever since.

While she may be imbued with respect for the great works of the European tradition, she does not do “after so and so” paintings, realizing that she must have an identification with her subject and create her own style of painting. She began with subjects from operas such as Salome and the Magic Flute. An avid reader of poetry, along with her composer husband, Younghee became fascinated with T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land, delving into its complex imagery with the help of various reader’s guides. About six years ago she started a series of drawings, monoprints and paintings inspired by The Waste Land. Eliot’s overlapping, faceted and layered structure offered a paradigm for the ambiguous structure she sought in her work. But each attempt involved a struggle, the struggle to suggest the specific image used by Eliot—the Cumean Sibyl, the drowned sailor Phlebas—without letting it become too literal, and to simultaneously evoke other fragmentary images and suggestions of setting while keeping the overlapping ebb and flow of the whole.

The complex relationship between 20th century poetry and painting abounds in instances of cross influences. Cubism not only shattered the guitar and wine bottle in painting, it broke up the novel’s narrative continuity and fractured the poetic stanza, while literary surrealism prompted visual artists to adopt automatism to mine the unconscious. In her series of paintings and drawings inspired by The Waste Land, Younghee attempts a fusion of Eliot’s structure and subject, reflecting his use of fragmentary parts that may constitute an entity, but can never be seen as a whole. In the same way that Eliot’s work consciously refers to its nature as a linguistic structure her drawings constantly refer to the act of drawing as a means of signifying and this is emphasized by the visibility of the cumulative and corrective processes that accompany it.

Her Waste Land series began with small pencil drawings in 1992. Five themes were selected as the core of the series: Philomel, the drowned Phoenician sailor, Mrs. Porter and her daughter, Madame Sosostris, and the seer Tiresias. Compositions based on these subjects were developed in drawings and paintings simultaneously while she continued to reread The Waste Land and explore its layered meanings.

The distinction between illustrating a literary work and working parallel to it revolves around the extent to which the verbal image is literally transcribed in visual form. The most literal image here, that of King Tereus cutting out the tongue of Philomel, was actually derived from a drawing the artist made at the Natural History Museum of a hawk seizing a smaller bird. This is typical of the way her drawings are laden with multiple powers of suggestion. Younghee uses figures in poses vaguely reminiscent of classical archetypes or invents a multi-figured scene of action that suggests a Mannerist “descent from the cross” in much the same way as Eliot incorporates phrases from a song or poem or drops in a name from a different time or place. Thus the drawings in this series simultaneously evoke an image from The Waste Land and are analogous to Eliot’s way of structuring his poem.

The artist’s dual East/West background may contribute to her capacity for such a mixture of certainty and ambiguity and to her ability to avoid circumscribing closure. Brought up in Korea until the age of fifteen, she learned oriental calligraphy and the formulas for painting rocks and flowers. “The study of traditional watercolors requires the practice of a lifetime—few master it and even fewer make poetry. The discipline of this approach has influenced the way I work,” she admits. At the same time it seemed to her very “exotic” to look at works by Michelangelo. “When I came to America I was busy assimilating the European tradition. It gave me fresh energy and I was immersed in it.” Not being too firmly rooted in one set of signifiers has freed her from a preconception of what a drawing should be and made it possible for her to work out an independent approach that may make reference to cubist markings, Renaissance figures, and the negative space of a Chinese landscape. Her feeling for the value of each mark her pencil or charcoal leaves on the paper surely comes from her practice of calligraphic brushwork. On the other hand the frequent overdrawing, erasures, and multiple outlines are antithetical to that tradition and more suggestive of twentieth century Western practice.

The ambition that flared in her two decades ago in Rome, to meet the challenge of the past while working with meaningful content for the present, has found fulfillment in these richly allusive drawings. The personal syntax Younghee has evolved expands the possibilities of this oldest of mediums.

Maine, March 1997

Martica Sawin is an Art historian and critic, most recent book:

Surrealism in Exile and the Beginning of the New York School,

MIT Press, 1995