1999, oil on linen, 23" x 26"

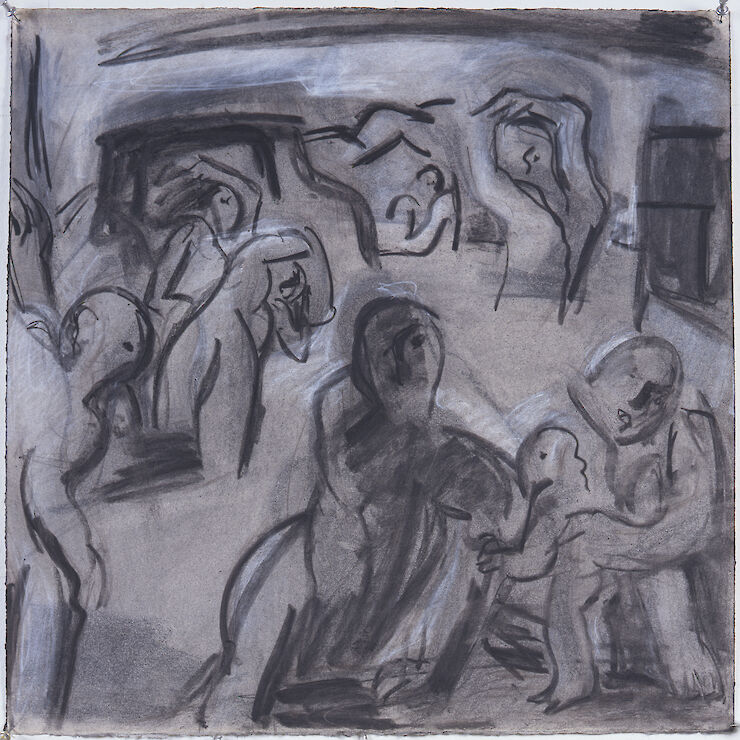

Faint Moonlight

- Year

- 1998

- Medium

- oil on linen

- Dimensions

- 22" x 25"

- Work Group

- The Waste Land

1998, oil on linen, 22" x 25"

A continuing problem for contemporary culture is the use of an employable past. This is particularly true of painting, where pressures have merged it with other media or undermined its once preeminent status. Even as we consider the bewildering amount of visual information and historical styles open to artists, we must problematically grapple with the destruction of the sublime, the ironic bracketing of authenticity and the proposed irrelevance of the “Old Masters.” In this regard, Younghee Choi Martin’s wonderful works stand out as a reminder of painting’s possibilities.

Choi Martin’s current body of paintings is based on T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land. Published in 1922, the poem is cited as the summit of both Anglo-American poetry and the culture of high Modernism. More importantly in this case, it is employed by Younghee as a philosophy and methodology addressing the act of painting. She seeks a working analogy with Eliot’s ideas, rather than to simply illustrate his poetry. The Waste Land’s classical allusions and mythic references to Virgil’s Aeneid, or Wagner’s Tristan and Isolde, for example, translate into the artist’s complex figurative compositions based on an intimate knowledge of master paintings. In this pursuit, she has assimilated a broad range of figurative gestures from Titian, Poussin and others. Her creative process is closely related to looking and interpreting, as well as executing hundreds of drawings. Rather than relying on a neo-classical language bound by conservative academism, the artist’s repertoire depends upon an improvisatory impulse. These works are dictated by feeling and intuition rather than mere knowledge, retaining their openness and wealth of association.

From each painting’s onset, the surface is reworked many times without the aid of models, photographs or other figurative accoutrements of observation. Note Waiting for Rain, 2003. Its tactile immediacy is derived from the gestural overall qualities of painterly abstraction. Like de Kooning, Younghee may also be called a “slipping glimpser,” but one who balances the painting process with an ongoing analysis of the literary text. Such a reliance on literature flies in the face of mid-century Greenbergian formalism with its presumptions of materiality, self sufficiency and abstract flatness. Her use of painting’s past, conceived without irony, circumvents much contemporary art based on post-Warholian pop culture. In other words, the categories Classical, modern or post-modern don’t particularly concern her. It is her intent to restore painting as a source of aesthetic resonance and reflection in the service of cultural renewal. This idea is not simply bound to our own time and place. At the beginning of the last century, Eliot and other artists shared similar aspirations in the hope of creating a new art. It was an art that paralleled the archaic works of the past, but echoed the minutiae of modern life. According to Eliot’s vision, Modern Art must go beyond the old dualities of past/present and subject/object in order to create a state of transcendence. One of his primary techniques was the introduction of multiple perspective within a single poetic narrative, fusing separate characters. This goal was historically concurrent with the planar overlapping and distortions of Cubism, as well as the Vorticism of Eliot’s own England.

Transcendence still provides a meaningful category for Younghee’s imagination. Rather than seeking it in the genre of landscape as many neo-romantic artists have done, she addresses a much more difficult territory. She mixes the pre-modern traditions of figurative construction within a fully saturated web of paint, made possible only after the advent of Cubism, Surrealism and the New York School. Each stroke describes a human referent pulled out of the void, even as memories of academic machines and cohesive figurative structures persist, confronting us with the limits of our own time, taste and presumptions. Her nudes are the result of a careful logic and working process. Much to our surprise, these deceptively simple accretions of paint stride, pose, languish, ponder, strain, or brandish dangerous intent, all within a believable but fictive space. Traces of their humanity are always present. Their gestures, relationships and haptic intervals are oddly parallel to Poussin’s careful rhythms and sculptured pictorial depths. As in traditional history painting, someone is doing something to someone else. Bodies and their interstices form a clear visual plane, rife with incident. They evoke Cezanne’s bathers or the prostitute/goddesses of Les Demoiselles d’Avignon: opaque, heavy limbed, filled with the gross materiality of paint as well as the medium’s inherent expressivity. Sometimes limbs and spaces firmly overlap in the equivalent of a Roman frieze, as in Sea Nymphs, 2004, or else fuse and meld into a surrealistic dance, in Inexplicable, 2002. At other times, calligraphic and gestural strokes knit the entire surface together, welding individual bodies into a single impenetrable mass: Gleaming Night, 2003. The paintings vary from each other, just as passages differ within a single work. The shift in figurative notation and the evocation of grand manner painting form the equivalent of Eliot’s multiple perspective and classical allusion.

In The Fall of Troy, 2004, the artist depicts Aeneas leaving the besieged city. As referenced by Eliot in The Waste Land, Aeneas must marry Lavinia to found Rome, yet he is already engaged in a liaison with Dido. Past and present converge, as the artist employs the motif of the World Trade Center’s charred grid in the lower right hand corner, tying the two eras together. Younghee subscribes to the classical idea that tragedy is best contained within an enclosed form, removed from gross emotionalism. It is a way we may contemplate horror without becoming enmeshed in it. Yet her nudes also have their joyful and hedonistic aspects. In Thunder of Spring, 2004, she depicts the ease and erotic pleasure of the body as in the tradition of Matisse or Gauguin. At its most radical, this approach propounds the utopian nature of the figure and its integral relationship to modernism. It is a tradition in which Younghee Choi Martin participates fully.

Examine the background of Thunder of Spring and notice the boats reminiscent of Raphael’s The Miraculous Draft of Fishes, 1514-15, or the gestures of Titian’s Bacchus and Ariadne, 1520-22. Placed into a generalized abstract structure, we no longer know what the narrative is. We merely hear its whisper. In this regard, openness is neither a simple function of form nor content, but the dynamic organizing principle stemming from the work’s inception.

A series of stunning smaller works highlight the artist as a jewel-like colorist, achieving maximum chromatic intensity through a few tones. The Moon Shone Bright, 2002, is awash with nocturnal light, communicating magical secrets of sex and death. Vernal Pool, 2003, achieves all the heft of a large figurative painting with a few carefully chosen smears of gray, russet and emerald green. Finally Inundation, 2003, is drenched in sunset beach light despite its non-naturalistic palette. All these works are smaller than 30 inches and pose a fascinating addendum to Choi Martin’s oeuvre by suggesting the grand tradition of masterworks through the most economic of means.

Language pushes us toward meaning, toward a coherence that does not exist in the real world. We prefer that our realities defer to the codes of language, to the discourses of formal structures, despite the dangers of their false presumptions and impressions. The strength of The Waste Land is that the poem renounces ultimate meanings and calls attention to the ways we read and make sense of the world. The Waste Land’s ultimate triumph is that, like James Joyce’s Ulysses, it resists the temptation to insert the coherence of language into the panoramas of myth, history and modern urban crowds, despite poetry’s pressure to do so. This is the hallmark of its modernism and the inspiration for the artistry of Younghee Choi Martin.

Younghee has achieved something marvelous with her paintings. The strength of the artist’s work is that she has successfully gone back to the creative sources of inspiration without being swallowed up by them. In this context, The Waste Land is a seminal text, but it leads to other texts. The “Old Masters” are great artists, but they are essentially the source material for other paintings. Her creative process is based on the confluence of text and image as she alludes to their mutual co-dependence and interchangeability. Choi Martin’s working relationship with The Waste Land has developed over 15 years of close reading. In that time she has produced a significant body of work. We may discern in her experience the ongoing relevance of modernity, the legacy of the 20th century and the continuity of painting’s glorious tradition. Yet even if these assumptions aren’t made, her message speaks with import and authority. Painting and reading are aspects of a single protean process, a hermeneutic of creative interpretation. The artist makes us aware that creativity is a defining act for herself and her audience, one arising from a historical context. Its nature is fluid and transformative, a power which cannot be reduced or deconstructed. She understands that its essential gift is one of freedom.

© Joel Silverstein 2004

View articleLooking at Younghee Choi Martin’s pencil drawing The Sibyl of Cumae one is at first reminded of the angled lines and shifting tonal areas of a cubist drawing. Then figures that might have come from Michelangelo’s Last Judgment become visible, then rocks and a figure half submerged in water. Finally there emerges a sense of some powerful emotional force to the shadowed foreground figure. These are drawings that release their meanings in sequential stages, drawings that pull the eye back again and again in search of an ultimate resolution that remains elusive.

Younghee’s drawings run parallel to her paintings. “I make drawings before, during and after my paintings. One enriches the other.” The refusal of a traditional relationship of preliminary drawing to final painting reflects the spontaneous, open-ended, and intuitive way she works in both media. Decisions are laid bare so that her considerable reworking, erasing, and layering are part of what the viewer is intended to grasp. The drawings are based as much on value contrast as on line and the lines are drawn several times over so that they too read as values. There are strong evocations of cubism here as well as of Cezanne, in the use of open forms, broken angular lines counterpoised with sections of curves, and tonal areas established in the Cezannesque manner of short parallel lines or strokes.

Running through her drawings is the hint of something previously seen, the suggestion of a kinship with Cezanne’s drawings of bathers or Titian’s late masterpiece, The Flaying of Marsyas. Such resonance is intentional and has been Younghee’s goal since spending her senior year of art school in Rome. She had already taken classes at the Brooklyn Museum Art School and had spent three years at Rhode Island School of Design, a summer at the Provincetown Art School and another summer at the Yale School in Norfolk. However, it was the challenge of the art that she saw in Rome that crystallized her goals—“I was moved by these monumental masterpieces. I wanted to do my own version of these great paintings and see if I could come anywhere close.”

When she returned to the United States, Younghee knew what she wanted to do and knew it would take several decades. She took on a full-time job, eventually becoming an art director at Vanity Fair, and painting at night and on weekends. By 1990 she had enough savings to finance three years of a full-time painting career. Thanks to several solo exhibitions in New York and a developing audience for her work in her native Korea, she has been able to pursue full time painting ever since.

While she may be imbued with respect for the great works of the European tradition, she does not do “after so and so” paintings, realizing that she must have an identification with her subject and create her own style of painting. She began with subjects from operas such as Salome and the Magic Flute. An avid reader of poetry, along with her composer husband, Younghee became fascinated with T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land, delving into its complex imagery with the help of various reader’s guides. About six years ago she started a series of drawings, monoprints and paintings inspired by The Waste Land. Eliot’s overlapping, faceted and layered structure offered a paradigm for the ambiguous structure she sought in her work. But each attempt involved a struggle, the struggle to suggest the specific image used by Eliot—the Cumean Sibyl, the drowned sailor Phlebas—without letting it become too literal, and to simultaneously evoke other fragmentary images and suggestions of setting while keeping the overlapping ebb and flow of the whole.

The complex relationship between 20th century poetry and painting abounds in instances of cross influences. Cubism not only shattered the guitar and wine bottle in painting, it broke up the novel’s narrative continuity and fractured the poetic stanza, while literary surrealism prompted visual artists to adopt automatism to mine the unconscious. In her series of paintings and drawings inspired by The Waste Land, Younghee attempts a fusion of Eliot’s structure and subject, reflecting his use of fragmentary parts that may constitute an entity, but can never be seen as a whole. In the same way that Eliot’s work consciously refers to its nature as a linguistic structure her drawings constantly refer to the act of drawing as a means of signifying and this is emphasized by the visibility of the cumulative and corrective processes that accompany it.

Her Waste Land series began with small pencil drawings in 1992. Five themes were selected as the core of the series: Philomel, the drowned Phoenician sailor, Mrs. Porter and her daughter, Madame Sosostris, and the seer Tiresias. Compositions based on these subjects were developed in drawings and paintings simultaneously while she continued to reread The Waste Land and explore its layered meanings.

The distinction between illustrating a literary work and working parallel to it revolves around the extent to which the verbal image is literally transcribed in visual form. The most literal image here, that of King Tereus cutting out the tongue of Philomel, was actually derived from a drawing the artist made at the Natural History Museum of a hawk seizing a smaller bird. This is typical of the way her drawings are laden with multiple powers of suggestion. Younghee uses figures in poses vaguely reminiscent of classical archetypes or invents a multi-figured scene of action that suggests a Mannerist “descent from the cross” in much the same way as Eliot incorporates phrases from a song or poem or drops in a name from a different time or place. Thus the drawings in this series simultaneously evoke an image from The Waste Land and are analogous to Eliot’s way of structuring his poem.

The artist’s dual East/West background may contribute to her capacity for such a mixture of certainty and ambiguity and to her ability to avoid circumscribing closure. Brought up in Korea until the age of fifteen, she learned oriental calligraphy and the formulas for painting rocks and flowers. “The study of traditional watercolors requires the practice of a lifetime—few master it and even fewer make poetry. The discipline of this approach has influenced the way I work,” she admits. At the same time it seemed to her very “exotic” to look at works by Michelangelo. “When I came to America I was busy assimilating the European tradition. It gave me fresh energy and I was immersed in it.” Not being too firmly rooted in one set of signifiers has freed her from a preconception of what a drawing should be and made it possible for her to work out an independent approach that may make reference to cubist markings, Renaissance figures, and the negative space of a Chinese landscape. Her feeling for the value of each mark her pencil or charcoal leaves on the paper surely comes from her practice of calligraphic brushwork. On the other hand the frequent overdrawing, erasures, and multiple outlines are antithetical to that tradition and more suggestive of twentieth century Western practice.

The ambition that flared in her two decades ago in Rome, to meet the challenge of the past while working with meaningful content for the present, has found fulfillment in these richly allusive drawings. The personal syntax Younghee has evolved expands the possibilities of this oldest of mediums.

Maine, March 1997

Martica Sawin is an Art historian and critic, most recent book:

Surrealism in Exile and the Beginning of the New York School,

MIT Press, 1995

The paintings of Younghee Choi Martin bring a refreshing frisson of drama to the contemporary scene. They are like slices of grand opera. The stories they tell are tragic and sensual: scenes of violence and lamentation, or sunlit, watery reveries. Legends are the templates from which her images, over months of revision and many layers of paint, come excitingly to life.

The Magic Flute inspired one series; Salome another. Eliot’s The Waste Land preoccupied her for years—a characteristic choice, with its blend of myth and modernity and its echoes of Tristan. Today she is mining the Aeneid. There is something akin to the music of Berlioz in her method: the startling gestures and colors, underpinned by classical discipline, and the ancient tales thereby made new. The Aeneid obsessed Berlioz too.

Younghee is a voyager between far-off lands, a New Yorker from Korea whose quest led to Rome; an artist from the 20th century who yearned for the full-blooded drama of past epochs. As a child in Korea she learned still-life painting and calligraphy. In Italy, Michelangelo and Raphael became lasting influences. The two peninsulas are alike, by the way, in their long, tragic histories, strong emotions and flavors, and zest for musical theater.

East and West, classical and cubist, Poussin and Cezanne: there are many facets to this original artist. Beyond scenarios and comparisons, however, is her mastery of color and form. You don’t have to know the plot of an opera to love the music, though it sounds even better if you do.

– Val Schaffner

View articleNEW YORK – Maurice Arlos Fine Art is proud to present a series of drawings and monumental paintings by Younghee Choi Martin, March 25th - April 28 th, 2002. The artist’s reception will be on Tuesday, March 26th, 2002, from 6 to 8 p.m. Gallery hours are Monday–Saturday, 11am–7pm.

This series of recent work is inspired by T. S. Eliot’s poem The Waste Land. The multi-faceted Western and Eastern literary underpinnings of Eliot’s work parallel Younghee’s tactile references to traditional and modern painting processes, which she successfully combines with contemporary intensity and meaning. Younghee’s paintings reorient us within a new tableau of imaginatively superreal space. Like the reading of Eliot’s beautiful, complex poem, Younghee’s compositions provide many satisfying interactions with each engagement.

The most immediately striking element of Younghee’s s paintings is their color. She skillfully manipulates the illuminated atmosphere of each landscape to reveal drama. Her figures, deftly integrated into her landscapes as both symbol and material, emerge in the same way her compositions do, over time, organically. Her rhythmic drawing style continuously informs her painting process and creates a dynamic ambiguity between painted surface and illusionistic depth.

Within Younghee’s imagery, allusive narratives exist among theatrical scenes, and the layers of reference range from the literary and specific—for example, Eliot’s Tiresias and Philomel appear in many compositions—to the personally mythic and mysterious. She presents us with emblematic personages such as the classically standing man, or seated woman, and the archetypical child with outstretched arms. Younghee’s paintings achieve the intensity of the emotions, thus translating Eliot’s enigmatic poem into a new, yet timeless, form.

Younghee Choi Martin has devoted her life to painting and has received numerous awards, including one from the National Endowment for the Arts. She has had solo shows in New York City, throughout the United States, Korea and Japan. Most recently, her painting By the Water from The Waste Land series was exhibited in the Musee d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris. She lives and paints in New York City.

View article1999, oil on linen, 23" x 26"

1997, charcoal on paper, 22" x 22"

1997, oil on linen, 42" x 36"

1996, oil on Reeves BFK paper, 22" x 30"

1996, pencil on terre verde paper, 14" x 14"

1995, oil on linen, 14" x 18"